Development of digitalisation in the financial sector (2024)

The Swiss financial centre has maintained a high level of innovation activity. In 2024, FINMA continued to respond swiftly and competently to enquiries from supervised institutions about innovative expansions to their business models and from new players wishing to enter the market.

Two applications submitted for DLT trading facilities

The Federal Act on the Adaptation of Federal Law to Developments in Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT Act) entered into force in 2021. In 2024, FINMA processed two licence applications for DLT trading facilities.

FINMA took this opportunity to clarify some important underlying issues. It stipulated that issuers also have typical issuer obligations for their DLT securities registered on DLT trading facilities. These include the duties of ad hoc publicity and the disclosure of management transactions. In addition, the regulation requires operators that have their settlement infrastructure on a public blockchain to take measures to contain operational risks. These include technical audits of the technology used such as the public blockchain itself and the source codes of smart contracts. These code audits help to detect security gaps or errors. Smart contracts are self-executing digital contracts that are stored on a blockchain and automatically executed under certain conditions.

The question of finality, i.e. when a disposal of DLT securities is legally effective, needs clarifying for DLT based settlement systems. It must take account of the technical peculiarity of entries in the blockchain never being one hundred percent final (legal finality vs. probabilistic finality of the blockchain). Here, FINMA requires operators of a DLT trading facility to issue clear, transparent and binding rules for participants. They must state clearly when the transfer of ownership becomes legally final. FINMA likewise attaches importance to an effective strategy with regard to business continuity management (BCM). Furthermore, precautions must be taken for the possible failure of a component of the DLT infrastructure. For a DLT-based settlement infrastructure, FINMA requires measures and rules setting out how to deal with the securities admitted to trading in the event of a dysfunctional network (e.g. declaration as invalid, reissue, alternative trading options, etc.). Both the participants and issuers must be included in the process here.

Finally, FINMA declared that foreign participants do not require any separate authorisation (remote member authorisation). However, a DLT trading facility must ensure that foreign non-private participants are adequately supervised and subject to equivalent regulatory obligations as Swiss participants.

Intensive supervision of institutions in the FinTech sector in accordance with Article 1b of the Banking Act

The supervision of institutions with FinTech licences in accordance with Article 1b of the BA, known as 1b institutions, also proved challenging in the year under review. The focus here was on protecting depositors due to the tight capital and liquidity situation of the institutions. These institutions are generally start-ups that, as expected, have major expenses for establishing themselves and entering the market, and initially have no or little income. Successful market entry depends on successful funding rounds and a viable business model. The business models lie in the payment services sector, where the market is competitive and the margins are small. It has been shown that business models that address a niche with a unique offering or specialised client segment can be successful.

FINMA required FinTech institutions to conduct ongoing capital and liquidity planning and be capable of identifying bottlenecks in good time. Nevertheless, some risky situations arose at several institutions in the year under review. The situation was frequently exacerbated due to the questionable intrinsic value assets in gone concern scenarios when companies had difficulties continuing their business activities and were forced to consider liquidation. This particularly affected the valuation of in-house software that in many cases constitutes a major asset and cannot be disposed of easily, especially under time pressure.

Expectations regarding stablecoin projects formulated

FINMA already published guidelines concerning a possible licensing requirement for issuers of stablecoins back in 2019 as a supplement to its guidelines on initial coin offerings. Furthermore, it stated in its 2021 Annual Report that according to the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) stablecoin issuers had to ensure that the identity of all holders of stablecoins was adequately verified by the issuer itself or by appropriately supervised financial intermediaries. Just as anonymous accounts are prohibited, so too are anonymous stablecoins.

FINMA consolidated the financial market requirements in the year under review by publishing Guidance 06/2024 and in particular drew the attention of the banks involved to the relevant risks. Stablecoins aim to represent an asset with low price volatility on a blockchain, which is generally done by pegging it to a national currency. In order to achieve this, holders of stablecoins normally have a redemption claim at any time towards the issuer. For this reason, these claims usually qualify as deposits under banking law. FINMA also underlined in its aforementioned guidance the growing money laundering, terrorist financing and sanction circumvention risks arising from the possibility of anonymous transfers of stablecoins.

FINMA also noted that various stablecoin issuers in Switzerland make use of default guarantees from banks, and therefore do not themselves require a licence under banking law. FINMA set out its minimum requirements concerning such default guarantees for the protection of stablecoin holders, and pointed to the remaining risks for clients and to operational, legal and reputational risks for the guaranteeing banks.

Within the framework of the ongoing regulatory project under the direction of the FDF and the State Secretariat for International Finance (SIF), FINMA called for the risks set out in the guidance to be adequately addressed.

Implementation of supervisory expectations in connection with staking

FINMA explained its practice with regard to staking services in Guidance 08/2023. Staking allows holders of certain cryptocurrencies to have these blocked in order to support the security and operation of a blockchain network. They receive a reward in return, often in the form of additional coins. During its onsite supervisory reviews in the year under review, FINMA found that clients were being made more aware of the risks and legal uncertainties associated with staking. However, in a number of cases their attention was not drawn sufficiently to the counterparty risk due to the legal uncertainty if a staking service provider were to fail. Furthermore, there was a routine lack of information about the specific risks of the individual blockchain technology.

Individual institutions also had gaps in the due diligence audit of the validator node operators involved and in the development of contingency scenarios if such a third-party provider were to fail. Finally, FINMA urged the institutions to supplement and regularly update their Digital Assets Resolution Package (DARP). The DARP serves the liquidator as a source of information in the event of bankruptcy for accessing the cryptoassets and correctly assigning and paying them out to the individual clients.

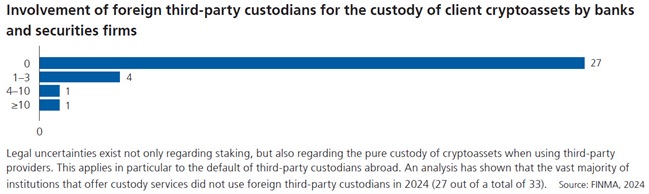

Another issue besides staking was the implementation of the requirements for foreign custodians. The financial institutions are required to ensure that custodians do not conduct their business activity without authorisation, that they are prudentially supervised abroad and that they operate in a jurisdiction that guarantees the same legal certainty as Switzerland regarding the treatment under bankruptcy law of cryptoassets held in custody.

(From the Annual Report 2024)